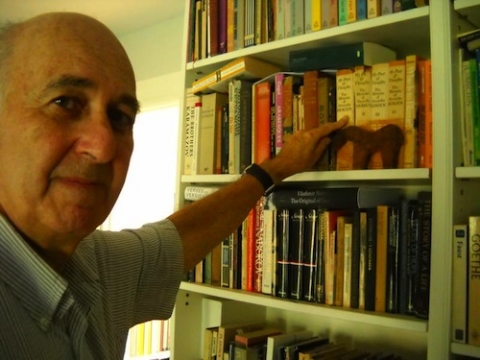

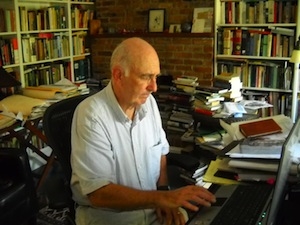

On a soupy July day in Brooklyn, Phillip Lopate leads me up the steps inside his home. All along the way to his third-floor office, we pass bookshelves. They’re everywhere—and then we get to his perch. The writer, known as a film critic, essayist, fiction writer, poet, and teacher, shows off the custom-built white bookcases that line this room’s four walls. Each case is jammed with books. Piles of more books stand on his desk, on the floor, on small tables. Even inside the fireplace serves as storage for magazines and videotapes. The room—in fact, his entire brownstone—overflows with stories well told and a lifetime of research and inspiration.

Below is a transcript of my audio interview with Lopate, which you can listen to by downloading the MP3 linked at the top of this page.

Phillip Lopate: This is my nest, my aerie. And it is like a kind of a tree house in the sense that I’m on a third floor and I look out on these trees across the way and surrounded by books, which is the way I like it. They say books do furnish a house, and that’s been my experience, certainly.

I would rather buy a book than borrow it from the library. I mark it up. And I used to get into arguments with my wife. She’s a painter and a graphic designer, and she would say, “We don’t have any room for paintings, for artworks. These books are taking over, you know?” But I tried to argue that this was my livelihood, this was a working library. These are not passively sitting there. These are books that I use again and again.

***

PL: Staring straight ahead, we have a shelf of essay books and nature writers. Nature writers are on the bottom because I’m not really a big fan of nature writing. They’re not at eye level, you might say.

TriQuarterly Online: Now tell me, are these books you’ve chosen essays from for your collection?

PL: I basically have these American essayists are living and dead, like A. J. Liebling or Edward Hoagland or M. F. K. Fisher. Then I have a whole slender bookcase that is just composed of books about New York City. My writing career has developed a lot of subspecialties. I’m considered someone who knows a fair amount about New York, so I have all these reference books and history books and so on that I pilfer shamelessly when I’m writing my own pieces about New York.

TQO: Are these books that you used when you were working on Waterfront?

PL: Absolutely, and also when I was doing my anthology Writing New York, about New York literature. There’s a whole bookcase full of film books, because film is another one of my areas of supposed expertise. I use them again and again in film pieces—again, reference books and also books of film criticism. I did the anthology American Movie Critics for Library of America, and I amassed a lot of these books at that time. And as you can see, they’re not only vertical but they’re horizontal on top, because I ran out of space. Next to them, don’t ask me why, is a bookcase that contains Japanese and Chinese books. I’m a real Japanophile, and I love Japanese literature. And then in the bottom shelves there’s American poetry.

TQO: Again, those are kind of out of sight. So is that something you don’t want to see so much?

PL: No, I’d love to see them. Again, there is this struggle between the books and the furniture. And my wife decided some of the chairs in the living room were too big for the scale of the living room, so she exiled them to my office. So now I have these big chairs. I don’t really need quite such big chairs—these big armchairs are blocking the views of some of the books. This is a struggle one has to endure, I guess. So sometimes when I have to get a book of poetry, I have to move the lamp or chair out of the way.

***

PL: In the other direction is a floor-to-ceiling massive bookcase that consists again of national book collections. In the first one is Russian literature, and then German literature, and then French literature, and then Italian literature. And running down the bottom two shelves is Spanish and Portuguese literature. And then there are these little areas like Danish and Swedish, Scandinavian literature, which I put under German literature because I thought that they bore something of a resemblance, you know?

PL: In the other direction is a floor-to-ceiling massive bookcase that consists again of national book collections. In the first one is Russian literature, and then German literature, and then French literature, and then Italian literature. And running down the bottom two shelves is Spanish and Portuguese literature. And then there are these little areas like Danish and Swedish, Scandinavian literature, which I put under German literature because I thought that they bore something of a resemblance, you know?

My favorite books are in this section, because I really fell in love with world literature when I became a writer—or when I wanted to become a writer—more so than with American literature. My whole reading pattern was to sort of live in a country for a while in my head and read the literature of that country. And so in a way it took me awhile to get to American literature.

TQO: Well, I know that Montaigne is one of your favorites, and there’s several of his right at eye level and fingertip . . .

PL: Yeah, Montaigne is perhaps my favorite. So I’ve got the Donald Frame translations. I’ve got the Screech translations. I’ve got Frame’s biography. Another Montaigne biography that is just about to come out by Sarah Bakewell, called How to Live, is very good. And there are some other books about Montaigne that I’ve used in my teaching.

TQO: Within a collection from each country or each genre, do you have a method of organizing them, alphabetical by author or title?

PL: They’re arranged alphabetically by author. It’s unsystematic, you might say, but there is a system in that it’s all alphabetical and I know I can put my hands on a book. It’s really not that hard. It really only takes me a minute to find anything.

***

PL: Now, turning to the other wall, the final of the four walls, I have dead Americans, you might say, because I have to put the living Americans down on another floor; I ran out of space here. Sometimes I have to move things around because someone dies. Like John Updike—I think he is still in my—oh no, he’s here in the dead writers. Wow. I’ve moved him from the living writers. That was very quick of me. Usually it takes a while. They usually live in a bit of limbo, you know, where they’re still in the live section and I haven’t moved them into the dead section.

TQO: Is there a section for Susan Sontag?

PL: Susan is now in dead Americans. As you can see on the next-to-top shelf, there’s a whole lot of her. But there’s always a kind of pressure to decommission books. Every year we have a stoop sale, and for that I try to comb through [and identify] things I’m not going to read again. The result is that over the years my collection has become more and more conservative or classical, because the books I’m likely not to read again, or not to consult again, are my contemporaries. You know, if it’s something like Heradotus, I never know if I’m going to be in that mood, or Carlyle or something like that. So I’m much better read in other centuries and dead authors, and I would say rather weak in contemporary literature.

TQO: And I see you have stacks of films as well. How do you have those organized?

PL: I haven’t figured out a way to store all the DVDs in one place. So for instance, if you poke your head around, you’ll see that at the edge of the bookcase there’s a very skinny bookcase that contains the DVDs from R to Z.

TQO: Are they organized by title or by director?

PL: By director—alphabetically by director. I’m enough of an auteurist that I want to keep the works by the same person in the same place.

Across the room I have DVDs that are essay films, or documentaries, because that became kind of a subspecialty. I’m thinking of writing a book about essay films.

TQO: How does a book merit being on your desk?

PL: I’m currently writing a chapter in a book about the Brooklyn Academy of Music, its 150th anniversary. I’m writing the first one hundred years. It’s a big responsibility. It involves a lot of Brooklyn history. It involves performance-arts history. It involves architecture. So I have The Encyclopedia of New York City there, I have a book on Brooklyn architecture, and I have a whole bunch of other materials that relate to the BAM project.

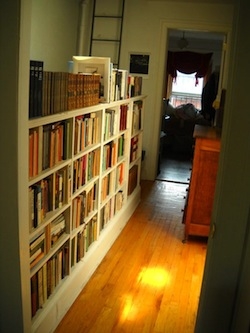

TQO: And behind me in the hallway there’s a whole lot of books too.

TQO: And behind me in the hallway there’s a whole lot of books too.

PL: Behind you in the hallway, there’s English literature. It begins with Ackerley and goes to Virginia Woolf, and I forget if I have any Z writer. But I also have a bunch of sets, and the sets tend to be put on the top or somewhere else. For instance, I have a whole set of Charles Lamb’s work. I also for some strange reason have a set Oliver Wendell Holmes’s prose works. You never know when you’re going to need that. And Samuel Beckett. The idea of Samuel Beckett’s collection next to Oliver Wendell Holmes boggles the mind. And next to them I have a collection of each one of my books. It was always my ambition to write a whole shelfful of books.

TQO: So you don’t keep your own books at the ready.

PL: They’re not in my office, but what I have in my office in that fireplace are magazines and books which have individual pieces of mine—not whole books

***

TQO: Now we’re on the landing. And how did you decide to put these books here?

PL: Well, we’ve got a whole hodgepodge of books here. Jewish literature, biblical literature, Indian literature, like R. K. Narayan, and Arab literature. Then there’s a lot of, I don’t know what to call it, but sociological, historical, and the next shelf is educational books. These are all educational books because that was a subspecialty of mine for while.

TQO: I see a book of yours, though, Being with Children.

PL: Yeah, yeah, I don’t know how that got in there, but anyway. Below them is a kind of shelf of Greek and Roman literature. Moving right along, there are a bunch of performance books, theater, jazz, playwriting. So this is truly a hodgepodge.

TQO: Fair enough.

PL: And then there’s a small case of DVDs, another case of DVDs, from F to the beginning of R.

***

PL: So now we’re going to go into my wife’s and my bedroom. Up above here, we have living fiction writers. We have four shelves of living fiction writers.

TQO: And whom do they include?

PL: Anyone from Anne Beatty to Jonathan Franzen, Jonathan Lethem, all the Jonathans—and James Salter and Philip Roth, and up here Toni Morrison and so on. Then there’s a shelf of memoirs, friends of mine like Molly Haskell, Emily Fox Gordon.

TQO: Tell me about these films.

PL: These are the final collections of DVDs, A through E or F, something like that.

TQO: And on each side of the bed there are reading materials on nightstands.

PL: That’s right, that’s right. My wife has a whole bunch of books, and I usually have a few magazines or books. Every day I try to read at least an hour, and I don’t do it for any other reason than that it keeps me sane. I need someone else to think thoughts for me. I don’t want to think all the time.

TQO: Well, it’s done a good job so far.

PL: Thank you.

PL: Now we’re in the first-floor living room. We have mostly art books here. They’re everything from, you know, de Kooning, Manet, David Smith, to Himalayan art. Anything you could imagine. Now we go to the last collection in the house, which I consult the least, I have to admit--the cookbooks in the kitchen. My wife loves cookbooks, and she has a wonderful collection. She loves the way good cookbooks look.

***

PL: And that’s about it, you know. Books everywhere! It’s all very organized. It doesn’t look organized, but it is organized.