The lessons come in the mail. Packages like gifts. When opened, there are capacitors, transistor sockets, and circuit board connectors, neatly arranged along with the assembly manuals. These my father will carefully follow, filling in the question-and-answer sections in his cramped script. He then returns them to the men at Bell & Howell in Chicago, prompting the next lesson to be sent. Pen pals writing to each other in secret code.

"If you’re handy with a set of tools, you may already have some of the skills you’ll need to build Bell & Howell’s color TV . . . the TV with digital features! This program is the perfect way to discover the exciting field of digital electronics.”

"If you’re handy with a set of tools, you may already have some of the skills you’ll need to build Bell & Howell’s color TV . . . the TV with digital features! This program is the perfect way to discover the exciting field of digital electronics.”

It is a code my father understands—that of improvement. Hunched over in the back bedroom of their small rented house, he builds. Before the TV, he must build a multimeter, which measures ohms, volts, and amps, and also an oscilloscope with a sine wave like the mountains and the sea. He’d rather be in the living room, with my mother, her hair tied back in a scarf as she nurses the baby on the secondhand couch with the Saturday afternoon sun coming through the windows. But he is building. What’s important is to be building.

“This Bell & Howell program is approved by the state approval agency for Veterans’ Benefits. Please check the box on the card for free information.”

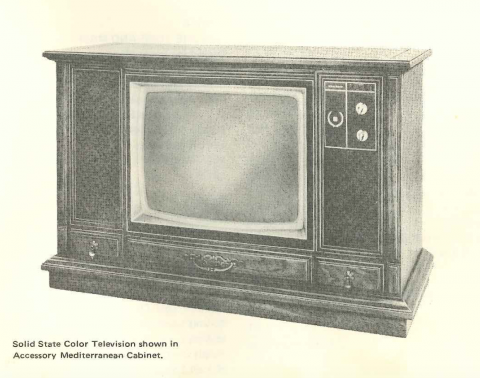

It takes my father over a year to complete. Many evenings, most Saturdays. “It was a much nicer TV than we could otherwise afford,” he says now. He felt he was getting away with something. The course cost $1,500! His future leisure paid for by the government—his way of stickin’ it to the man.

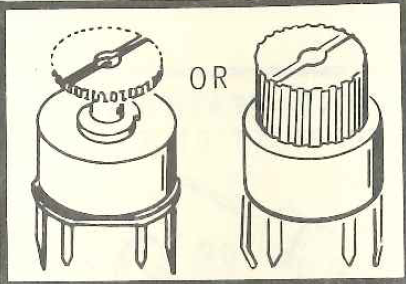

“Resistance is the opposition to current. Resistance is measured in Ohms (Ω).”

“Resistance is the opposition to current. Resistance is measured in Ohms (Ω).”

“One of my classmates built one. Also, a guy at work. Do you remember him?” my father asks my mother. “His wife died so young of cancer.” Oh yes, she remembers, so sad. They both pause for a moment.

For years my brother kept the oscilloscope on a shelf in his bedroom. We believed it was searching for transmissions from outer space.

On the solid-state color TV we watched Scooby. We watched the annual primetime showing of The Sound of Music with popcorn while my mother sang along. We learned the Super Bowl Shuffle.

“Needless to say, this is one of our largest do-it-yourself kits. Therefore, we believe it appropriate at this time to emphasize the need for careful workmanship and observations of the instructions as you build.”

He smokes a cigarette as he works, something he will soon quit cold turkey, along with coffee. No room for these vices in the life he is building. When he has all of the hardware in place—the curved, slightly green, glass screen, the picture tube, and the many, many circuit boards—it is time to turn it on.

Alone, in the back room, he plugs it in and pushes the button, then stands back. Nothing. He fiddles with the button. Nothing. He fiddles with the tube. Nothing. He calls the guy from work, but he has nothing helpful to say. So my father gets out the multimeter and begins checking the connections one by one by one. This is how you build something.

“START: 2200 Ω (red-red-red) resistor: CA-4 (S-4) to CB-3 (S-1). Use ½” of small sleaving on the indicated lead.”

The static buzz of the homemade machine is beautiful. The thick sound of order. Forget the army. Forget smoking cigarettes and garage sale furniture. He calls my mother to come look. She is wearing a gold skirt she has sewn herself. They stand side by side in the white glow.

In celebration, my father does something uncharacteristic. He orders a fancy wooden cabinet from the Bell & Howell catalogue to house the TV, which will leave a permanent rectangular indentation in the carpet.

On this screen my father will witness the significant moments of his time: the U.S. embassy seized in Tehran, Baby Jessica, countless house fires in surrounding towns, Madonna, the flood of ’93, election after election.

The meticulous construction and the wooden adornment are belied by the images that flicker like candy on the screen. But, looking down at his creation, my father understands how everything fits together. For one moment—one still frame—my father can see through the TV like a crystal ball, and he feels certain that finally all is in place. He knows everything he will ever need to know, has all he will ever desire: a wife, a child, a color TV. But then the images start up moving again, this time faster and faster.

(Note: Pictures are scans from Bell & Howell instruction manuals. Quotations are drawn from the manuals or from a magazine advertisement for Bell & Howell.)