A woman, alone, embroiders a bumble bee onto a pillowcase and, while doing so, she recalls the first play she ever saw, how she once terrified a young rival into leaving town, how she seduced the married man by a public fountain. Life of a Star by Jane Unrue is the story of a woman embroidering her life. The unnamed female narrator reveals to the reader that, though she was never a professional actress, acting has deeply influenced her. As a child she constantly noted the way others were perceived and, in doing so, learned how to control the ways in which she was perceived. Her remembrances are peppered with stage directions, such as in an argument with her mother: “And I hate (looked:sink) you (mirror) too! (Floor.)” Her mother was a professional actress, but the narrator uses the craft of acting as a lifestyle choice rather than a profession. Instead of making money off her acting skills, she makes relationships.

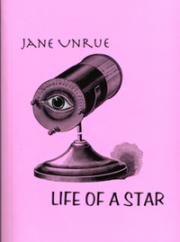

Life of a Star

By Jane Unrue

Burning Deck Books

The most emotional recollections are those surrounding an unnamed ex-lover, a married man. These moments, as all moments in the book, are recalled out-of-order, but the encounters with the lover are differentiated in that they are numbered in chronological order: “Encounter number four. ‘You’re right,’ I said, (chin tuck), ‘I haven’t told you much about myself’ (syllabic lateral movement of the head on much about myself).” The narrator uses the same self-employed stage directions with the man she loves and she did with her mother, constantly manipulating the distance between herself and the other through this carefully constructed artifice.

The novel unfolds as a series of disjointed thoughts, images, scenes, and memories. The book is 112 pages long, but may be read in a single sitting. No scene lasts for more than a page and a half, and an entire page may contain only a single sentence:

“It seems I have no feelings I can call my own.”

“New needle. (Bigger eye.)”

“Black satin thread emerges through a tiny hole: beginnings of a body.”

When multiple sentences do appear on the same page the language goes to the opposite extreme, becoming complex and lyrical: “Retracing all your steps along the corridor of trees, to search for an escape look up and see if you can find a dirty-looking star above this dead-eyes image of a garden conjured as if just to keep you from returning to the woman underneath you in your bed and telling her that it was only sadness for the many losses in your life, the many tragedies you’ve see, that caused your gaze to wander toward the wall.” It becomes difficult to get your bearings in a sentence such as that, especially in the middle of a story that is being told unchronologically by an unreliable narrator. It becomes essential, then, to approach the novel as you would a poem, to untether yourself from the presumptions of narrative and allow the sentences to grab you and pull you along like a riptide.

When the narrator decides she wants to close her self-created dramatic distance she finds herself unable to do so, commenting “it’s always stumped me why so many of my very most tender and authentic memories are tangled up with over-practiced words and stiff, exaggerated moves.” Having practiced fake emotion so well for so long, she has robbed herself of the ability to show genuine emotion in a genuine moment. This touches on an even greater question: is it possible to react genuinely once you’ve peered behind the curtain and seen the power of staged drama?

Ultimately, the narrator discovers through her musing both that she desires emotional intimacy and that she absolutely cannot have it. And even as she recalls her life to the faceless reader, she ponders the question, “I wonder if I’m acting now.”