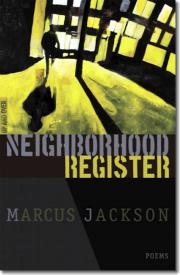

Neighborhood Register

by Marcus Jackson

CavanKerry Press

For his freshman collection of poems, Neighborhood Register, Marcus Jackson eloquently establishes a time and place: the American Rust Belt of his adolescence during the late twentieth century. He takes readers back to a time when “morning light / caught in your curls like barbwire,” when pagers were popular and eighth-grade English seemed pointless. Jackson ends the collection with his escape to college in New York City after graduating from high school.

Although the collection is presented as autobiographical, Jackson’s poems are not confined to his own experiences. For example, some of the poems predate Jackson’s birth and awareness, such as “Freshman Audition,” an homage to his mother when she was younger, and “Escape, 1961,” a look into his father’s affair and second family.

Jackson creates a positive identity as a young man growing up in a run-down neighborhood. He offers deep meditations on the everyday on the seamier side of the tracks, defending blunts, 40s, double negatives, and stolen cars, and giving them new insight. For instance, he ends his poem “Heartbeat by Way of a Blunt”—about getting high—with profundity and grace:

wallpaper breaks

an atom at a time from its glue;

your heart is a fist

something has tricked

to knock a century on the same door.

Jackson’s language is fresh and commanding. In “Speech Therapy” he asserts, “Ain’t nothing wrong with double negatives.” He argues:

You breathe better

when your throat’s welcome

to untunnel

the no’s and not’s that stockpile

during even a week a’ heartbeat.

The alliterations, rhythms, internal rhymes, and sound in his work demonstrate that Jackson is clearly a poet in tune with language. Language itself becomes the focus of his poetry at times; in “Eighth Grade Grammar,” Jackson lauds his English teacher, Mr. Bernard, asking,

How would we have known

to merit . . .

a man assigned to somehow

recouple the muddled

boxcars of our clauses,

to remeter our words

so the world might better hear us?

Not only does Jackson appreciate language and those who fight for it, he also attacks those who condemn poetry that he believes is worthwhile. “Poet’s Condolences to Critics” begins sarcastically with

Complete pity

your delicate skin forbids you

from the June sun strumming

every atom in this public park.

In this and other poems, his thick sarcasm, wit, and passion sing of a life he loves. This includes a love for his community; in “Ode to Kool-Aid,” Jackson discusses the drink’s various uses within his world, where Sandra from ninth grade “employed a jug of Black Cherry / to dye her straightened / bangs burgundy” and when “Granddad takes out his teeth / to make more mouth to admit [Kool-Aid].” He uses the first-person plural to tie himself to this communal consumption of Kool-Aid:

We need factory-crafted packets,

unpronounceable ingredients

a logo cute enough to hug,

a drink unnaturally sweet

This shared experience, albeit potentially hazardous to one’s health, is gladly imparted to readers.

Jackson’s collection includes many other odes as well: “Ode to the Scholarship,” “Ode to Last Call,” “Ode to the Hater.” In fact, nearly every poem in the book celebrates the reality of life at hand, his own and his community’s.

Neighborhood Register is an account of empowerment in spite of poverty, family turmoil, and decay. The book is a testament to how life can thrive, how folks can, as he puts it in a poem set in a Columbia College Students of Color bowling party after his arrival in New York, “aim between gutters.”