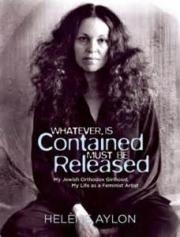

Whatever Is Contained Must Be Released

by Helene Aylon

Feminist Press at City University of New York

I found Whatever Is Contained Must Be Released while browsing in a feminist bookstore in Chicago and have since been unable to put it down. It is a memoir by a visual artist that is a mixture of art, literature, and political manifesto, and it is unlike any book of contemporary nonfiction I have read in recent years.

That’s because the memoir, like the artist herself, swerves between cutting-edge installation art, the ancient passages of the Bible, and centuries-old Jewish law and tradition. In one of Aylon’s major works, The Liberation of God, she highlighted passages of the Bible that bothered her; slowly it evolved until she put God on trial. Religious Jews don’t write in the Bible at all, so that project skirted the line between art and heresy.

Aylon’s work has been exhibited and collected by the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Jewish Museum, and the Warhol Museum. Her installation commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Hiroshima/Nagasaki appeared on a billboard in Times Square. But her most interesting art and writing seems to stem from her early life at the epicenter of Orthodox Judaism. She describes her family home thus: “The house we rented for eighty years was on the same block where the annual Simchat Torah (Joy of Torah) holiday dancing took place. Our street, Forty-Seventh Street, was the Times Square of Boro Park. The police barriers that were erected during the holiday to block traffic from entering the street were completely unnecessary because the streets were automatically emptied of cars on Shabbos and Jewish holidays. After all, the entire neighborhood was Orthodox.”

At nineteen, Aylon married a rabbi and moved to Montreal. She had two children, but soon, tragedy struck; her husband was diagnosed with cancer. At thirty Aylon became a widow. She enrolled in Brooklyn College and eventually allowed herself to be an art major. She writes:

I secretly enrolled in an acting class, but my major was art. Better late than never.

My degree in art would be a degree in freedom. I used my maiden name when I enrolled; I had yet to start using Aylon, and it was important to me not to “soil” the distinguished name of Rabbi Mandel H. Fisch [her husband] by exposing it to my secular, collegiate world. I cringe even now as I think about this. By the time I graduated Mandel had died, but I had a long way to go before I would truly no longer be Mrs. Mandel Fisch. My feelings were deeply conflicted. I did not take a picture for the yearbook, lest someone from home recognize me and reveal my identity to my professors and classmates. I did not want that old world to be part of my new one. It was only at the age of sixty that I dared to “come out” as a formerly Orthodox Jew.

But there, at Brooklyn College, she was lucky: her teacher was the great modernist Ad Reinhardt. One of the delicious pleasures of this book is that it reproduces two handwritten postcards from Reinhardt, asking how Aylon is doing after graduation and why she did not share the details of her life with him.

This memoir answers Reinhardt’s question as it tells the story, complete with photographs, art, and documents, of how one woman became an artist—and became herself—despite tremendous family and community pressure to do otherwise. It was not easy. Not long after her husband’s untimely death, she volunteered at a center for high school dropouts. There she met a psychologist who promised to cure her of her “religious paralysis.” He declared that it would be a change as momentous as losing her virginity. One afternoon, he took her out for a drive and began speeding—“leering up at the heavens, as the wind hit our faces, ‘You Lordy Lord up there, you fuck-up! Why did you let the babies die?’”

It goes on, getting increasingly lewd, with Aylon begging him to slow down and him yelling at God. Finally, she begins laughing hysterically. “That’s when he finally slowed down and drove to an exit to park the car. Then, with utter calm, he turned to me and declared that my nervous laughter was the release he was waiting for, that I was cured of what he called my ‘religious paralysis,’ and now I could get on with changing my life.”

Changing her life meant creating both her own sense of Judaism and her sense of herself as an artist. Her first professional commission was a mural on the doors of the Jewish chapel at Kennedy Airport in New York. She writes:

I knew that I wanted to paint one word on that chapel: Ruach. . . . It means spirit, breath, wind. It is the one word in the Old Testament that I still venerate. It comes from the second verse in the Book of Genesis that I spoke about with Mark Rothko: “In the beginning, God created heaven and earth. Now the earth was unformed and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep and the spirit [wind/breath] of God hovered over the face of the waters.”

Here Aylon quotes a first- or second-century sage. “Rabbi Akiva, the great Jewish scholar, once said that the world is based on wind/breath. ‘Take away just breath . . . there is no life.’ This word would be what I would hold onto as I exited one life and passed through the revolving door to face a new direction.”

Unfortunately, the donor who funded the doors wanted his name on them. Aylon refused. “I said, ‘This is the entrance to God’s temple. The name of the donor can be placed on a plaque somewhere on a wall.’” She writes that she had the courage to do this because she had already been paid for the doors, and photographs of them had been published in Art News. But when Aylon stopped by with her son to see the doors, she saw that they were “lying on the ground like fallen angels.” In their place, “an expensive new wooden entrance with the name of the donor on the new door” was there. “Two more words had been added: ‘push’ and ;pull.’” Aghast, Aylon paid four construction workers to pick up her doors and transport them to her studio in St Mark’s Place.

The doors remained there, in her studio. “The doors were there in the evenings when I went home to Brooklyn to give my daughter dinner and be a mother, and they greeted me upon my return the next morning, bearing witness to my life as an artist.”

This was only the beginning of the story of her career: both a battle with and a deep engagement with Jewish text and the Jewish community. What began with Ruach, those airport doors, culminated with a huge project later in her career. From 1990 to 1996, Aylon worked on a mixed-media project called The Liberation of God that took her interest in Genesis—and the entire Bible—to new levels. This breadth helps explain the intellectual challenge of reading this memoir; it includes plenty of references to centuries-old Jewish thought, and sometimes it gets a little esoteric. As I got deeper into this memoir, I found myself having to stop reading, to take a breath. It is an intense reading experience—at times a little too intense. But mostly, the book moves in interesting and graceful loops between art, theology, and memoir.

I wondered whether anyone who was not an artist from a religious background would appreciate this book. Then I saw the photo of Leah Rabin, wife of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was assassinated by a religious extremist, with Aylon at the Liberation of God exhibit. Leah Rabin, of all people, probably understood the fearsome power of religion and might be able to convince others that this unusual book matters. But as I reread, I realized that there was no need to name-drop. While there is plenty of radical art and opinion in these pages, there is something in Aylon’s brave, lonely, and stubborn struggle to become herself that is, in the end, universal. There is something profoundly human in the idea of what we contain, and what we eventually release to the world.