Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s second collection of poetry, My Funeral Gondola, was recently released by Manoa Books as the latest volume in its El Léon Literary Arts series. Her book is a cross-cultural, multisensory meditation on the intersection of death and life, using as its point of entry a powerful, poignant episode in musical history.

Fiona Sze-Lorrain’s second collection of poetry, My Funeral Gondola, was recently released by Manoa Books as the latest volume in its El Léon Literary Arts series. Her book is a cross-cultural, multisensory meditation on the intersection of death and life, using as its point of entry a powerful, poignant episode in musical history.

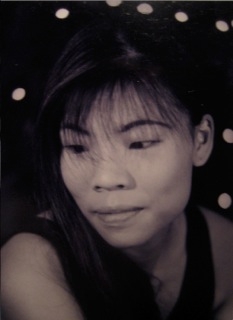

Born in Singapore to Chinese parents, Sze-Lorrain received a British education before going to the United States to attend Columbia and New York University. From there she moved to Paris, where she received her PhD from Paris IV-Sorbonne. Her consequent facility in English, French, and Chinese and her multiple expatriate experiences give her work a cultural and linguistic savvy that probes traditional notions of place and self.

After publishing her first collection of poetry, Water the Moon, Sze-Lorrain went on to translate books of contemporary Chinese poets and coedit the anthologies Sky Lanterns: New Poetry from China, Formosa and Beyond and On Freedom: Spirit, Art and State. A founding editor of Cerise Press and a contributing editor of Mānoa: A Pacific Journal of International Writing, she works as a cultural critic and an editor at Vif Éditions in Paris.

I recently interviewed Sze-Lorrain via e-mail to discuss her new book.

TriQuarterly: The title of your collection, My Funeral Gondola, alludes to a fascinating and rich piece of musical history. How did the idea for this title come about?

Fiona Sze-Lorrain: When I wrote the poem, I had no idea that it would be the title of the collection. I showed the poem to a trustworthy poet friend. She responded to its title with immediate enthusiasm. I was surprised, and sat down thinking about its resonance.

I often listen to Liszt’s La lugubre gondola, and elegies—cello, harp, piano, voice . . . but that winter I started to reconsider water as a symbolic element for movement or flexibility. I say “reconsider” because the first collection happens to be titled Water the Moon, though for me there is not much of a resemblance between the two volumes. In My Funeral Gondola I sought a different voice, different linguistic distance, texture, and emotional weight. At that time, I was also working on the French translation of Mark Strand’s Almost Invisible (Presque invisible). The idea of an afterlife—and our vulnerability when all of this earthly existence could be gone in a flash—kept recurring to me.

TQ: And how did it shape the poems you wrote for it?

FSL: It put in place a color palette for other poems. The humor too, I hope. It also helped me to create possibilities that could subvert proximity and intimacy. Although the thematic breadth emerged first with the scene of my funeral—a tragicomedy—by turns of irony, it has helped to veer the persona(e) away from melancholia or languidness. I sincerely hope the poems suggest a more reflective space than a reactive option.

TQ: A reflective space for the reader or you the poet?

FSL: Ideally both—but I can only speak for myself when writing the poems. It would be rude of me to even evoke the notion of a reader in ways that might anticipate or imply the “potential” of the text. The reflective space I sought is one that allows the via contemplativa to dialogue or check in with the via activa. The shape or form of a poem does depend on the level of listening, if only we listen hard enough. But this reflective space isn’t just about the quiet; it could come in the guise of a dramatic monologue, for instance. In this sense it differs from say, a prayer: it is less committed to the idea of living a credo or being corrective in expectations.

Smile in progress, but

no emotion.

. . .

My skin takes thoughts

away from light.

Before this mirror, I am my painter,

realizing that bareness

opens

and never shuts.

(“My Nudity”)

TQ: How does your sense of audience affect your writing?

FSL: I am interested in reciprocity and admire poems that take care of responses. I used to think of audience as being far on the receiving end, but I have realized that this is just a naive way of staying in a comfort zone. It is like shirking accountability. I find the intrigue of a poem’s afterlife humbling; it helps me keep a grip—and check—on any emotional “attachment” to the text at the time of writing.

TQ: Threads of grief weave throughout this collection. Do you consider the book, or any of the poems in it, to be an elegy? How does the poetry in the collection speak to your own experience of loss or your ideas about death?

FSL: Some poems are elegies. Or at least they started off as elegies. They speak directly to my experience of loss and recovery. I am less inclined to acknowledge the redemptive aspect of grief—the idea of self-absolution may be misunderstood as some gentle “encouragement” to feel better with regrets—though I try my best to go beyond its reckoning. Perhaps this is why I chose Nazim Hikmet for my epigraph—the irony of desiring longevity in a mortal world points back to the absurdity and illusion of what we believe to be closure.

TQ: Have you ever been to Venice yourself? If so, did your experience or memory—or imagination—of the city influence these poems in any way?

FSL: It makes me happy that you mention Italy. I have stayed in Milan and the Lombardian region but have never visited Venice. At the moment I am learning Italian. I would very much like to visit Venice, try more Italian recipes, and write more love poems.

TQ: You are also a highly accomplished concertist, and I understand one of the few who play the ancient Chinese zither professionally. You have clearly spent many hours practicing your instrument. How has this affected the process by which you write poetry? How has it affected your style?

FSL: Thank you for this question. Wish I knew!

Technical aspects of musical interpretation—pedaling, rubato, leggiero—help me work on a poem’s structural character (verse, stanza, or its inner breathing) from another angle. I began formal piano studies at the age of four and was trained in the French tradition of pianism. So the style of jeu perlé has conditioned my ear when it comes to clarity and discretion as possibilities of lyricism. Overall, however, I don’t see music as something disparate from writing. In poetry I read the character of music, and vice versa. Narratives and historical accountability exist in my work as a harpist. So I find ways to honor a common—though not necessarily harmonious—spatiotemporal environment. It comes with luck. Pain, yes. Mostly slowing down.

TQ: Your native language is Chinese, your everyday language is French—as you live in Paris—and you write poetry in English. Why have you chosen English as the linguistic medium of your poems? Or should I ask, how did the English language choose you? How does your multilingualism affect your poetry?

FSL: My native language isn’t just Chinese. I grew up in a hybridity of languages. A mix of each—such that I don’t know if I have a native language after all.

Although I look Asian, I am not a Chinese by nationality. I am fluent in the language—only because it was important to my family, when I was a child, that I learn it well—but whenever I speak it, my mind is translating it from English or French. My relationship with the Chinese language is a difficult one—in part because I don’t find it exotic. I was born in Singapore to diasporic Chinese parents but have an alienated understanding of the country and its culture; I live in France because I am a Francophone and in exile. Perhaps this is why I have chosen English as the linguistic medium for poetry. One of the prose pieces in My Funeral Gondola, “Return to Self,” says:

These days I speak English to a French mirror. When I exhale, the consonants shrink into an outlaw I bedded when the moon was old.

I write nonfiction in French and have tried writing poems in French. Abstractions came to me in French more easily than images, and that wasn’t what I hoped for in poetry. I wanted an intimacy, and a velocity in lyricism that could authentify the thoughts before and during—or even after—the writing. Some mourning took place while I was working on My Funeral Gondola, with the realization that all this while I’ve been “showing off” through words—imagination, “art,” and all that stuff. I felt so ashamed of myself, then sad . . . very sad, and for a long time. Writing poetry—and in English—forces me to confront this. This may have something to do with French being my everyday language. It isn’t a comfortable experience, and it carries an existential weight. In English I can better hear or create silence: a silence that is neither the inability nor the absence of communication. In English, I—others, too—see my imperfections more clearly:

Scooping up handfuls of fresh

silence from a mirror of oblivion,

I gather from the well

that night disguises his guests.

It pleases him that wind

must wait. Even rain. Misled,

the tempered dark takes a false

step. So many shadows,

so few ghosts—I am lonely

but curious

in this imperfect end.

(“After the Moon”)

TQ: Tell me about your poetic influences.

FSL: I am embarrassed to confess that I read more prose and plays—probably music, too—than poetry. I read Proust every year and am still reading the same Bach sinfonias as when I was nine. Preferences also include various translations of Buddhist scriptures and Latin texts. I recently read Hammarskjöld (in Auden’s translation) and Elfriede Jelinek’s Princess Plays. (Jackie, which is part of Jelinek’s Princess Plays, was on show at Théâtre Gérald-Philipe this April. It is now playing off-Broadway in New York, as a Women’s Project production.) But to answer your question, here are some of my poetic likes: Bashō, Milosz, Lorca, Miron Białoszewski, Eugenio Montale, Emily Dickinson, Tao Yuanming . . .

TQ: Are there Chinese, French, and English/American poets who have influenced you?

FSL: Other than the ones mentioned above—Joan Mitchell. She is a painter, but her work taught me how to approach writing as an expression and a form of expressiveness. Her paintings introduce me to colors, the outbursts of energy and stilled visual scenes in poetry from a different dynamics. So much passion and sincerity lives in her art.

I like poetry that isn’t a mental conception or “something that just takes place in the head.” Perhaps my failing—but I can’t believe in “imagination” when it happens as a choice of nonengagement with experience or the real. It is a question of ethics. The real has nothing to do with the limits of autobiography, but the unreal—surprise!—can be a manifestation of autobiographical maskings. Poetic imagination seems to travel further when it is a search, as opposed to being a result. Not the absolute truth but a practice in truthfulness. Please do not accept these as facts. They are just my thoughts, a work in progress.

In French literature, I revisit Rimbaud and Victor Hugo. They are my literary heroes. They write the way they live—not the other way round.

TQ: Has the poetry of any one language influenced you more than the others?

FSL: Alas, the choice of language hasn’t privileged its poetic influence on me. I do wonder from time to time what it feels like to be influenced by poetry of one particular language—or culture.