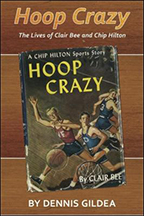

Was Clair Bee “America’s greatest forgotten coach?” Or was he a cheater and a hypocrite? Those are the questions Dennis Gildea sets out to answer in his new book “Hoop Crazy: The Lives of Clair Bee and Chip Hilton" (University of Arkansas Press).

Was Clair Bee “America’s greatest forgotten coach?” Or was he a cheater and a hypocrite? Those are the questions Dennis Gildea sets out to answer in his new book “Hoop Crazy: The Lives of Clair Bee and Chip Hilton" (University of Arkansas Press).

Though Bee did many other things in a long and productive life, he is best known today by the millions of baby boomers who, like me, read his “Chip Hilton” series of books about the life and times of a teen sports star.

Gildea tackles the problem of the seeming contrast between Bee as author—with Hilton as the idealized, squeaky-clean, too-good-to-be-true hero of these books—and Bee, the coach with a “win-'em-all obsession [ . . . ] who at times ignored or side-stepped the NCAA’s rules.”

As a coach Clair Bee, who is enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, has a better winning percentage (.827) than any other Hall-of-Fame coach. But his college coaching career ended in 1951, when a number of his players were caught up in a gamblers’ point-shaving scandal that nearly brought down the entire edifice of college basketball. Several of them served prison terms, and Long Island University (LIU), where Bee was coach and athletic director, canceled its entire sports program for six years.

On the Bee-as-charlatan side, Gildea quotes sports historian Albert Figone: “LIU’s role in the 1951 basketball scandal is the story of a brilliant coach who operated a corrupt basketball program by shielding his eyes from the truth with self-serving excuses and justifications, all the while fictionally portraying an idealized version of himself that had never and could never exist in college basketball.”

On the other side is Mike Lupica in a New York Daily News obituary column: “The story of the old man’s life is merely the history of basketball in this country.” And highly acclaimed coach and current basketball broadcaster Bobby Knight, to whom Bee was a mentor and close friend: “The first time I met Clair Bee my impression was that he was a brilliant man,” Knight told a reporter in 1979. “It wouldn’t take anyone long to see that he had a clear, precise mind that focused on every aspect of the game.”

After receiving a reviewer’s copy of the book, I clumped down my basement steps, and there, on the bottom shelf, way back in the corner, was Hoop Crazy by Clair Bee, the book Gildea ranks as Bee’s best in the twenty-four-volume “Chip Hilton” series. In a rereading I found it quite rewarding, if for no other reason than that it had Chip, his coach, and his team standing up for their only nonwhite teammate, an African American whom an opposing team threatened to exclude from a game. The book was written in 1950, well before segregation was ended in high school and college sports (see my earlier review of Ramblers, a book that delves deeply into the subject of race and basketball).

There’s something about basketball that gets people addicted. (See Cheech & Chong’s “Basketball Jones” for a great comic take on this idea.) I’ll have to admit that I’m an addict. One recent weekend, with my wife out of town, I watched games Saturday morning and afternoon (sometimes two at a time, one on TV and one streaming on the computer), and Sunday, after playing for two hours (we call it “geezerball,” but it has some striking similarities to real basketball, and we even run up and down the court at times), I took in another couple of games.

Yes, I still play at least twice a week, watch too much on TV, go to college and pro games when I can, and even coached my son’s “biddy basketball” team for a couple of years. Then there was a two-year period when I worked as a stringer for a small-town daily newspaper in Indiana, covering high school games.

It started when I was five years old and my dad began taking me to local high school games. Basketball was an all-consuming interest in Central Illinois communities in those days, and our local Purple Panthers weren’t too bad. I loved the noise, the hoopla, the drama and excitement.

It made me a prime target for “Chip Hilton” books. I’m not sure when I started reading them (probably in the early ‘60s), but the two I still have are both about basketball, despite the series being evenly divided between that and football and baseball—of course, Chip was a three-letter man every year, in high school and college.

I called Cliff Shehorn, an old friend from our teenage days who lived down the street from me in Litchfield, Illinois, and who shared my passion for basketball—and for Chip Hilton.

“Those books were fun,” he said. “Kinda like our own life in a way. It felt good to read those books. You could really put yourself in the book.” Not as Chip—we agreed he was too good an athlete to identify with—but perhaps as one of his buddies. In fact, though we loved the books, we did make fun of the Chip character as being too good and too goody-good. The Hilton books were also educational. Bee often included detailed exposition of strategy and tactics, including actual play diagrams.

In his book Gildea delves deeply into the historical record to answer the central questions he poses, but he tells us at the outset that he’s in Bee’s corner, though he didn’t start out there. In great detail (there are forty-five pages of note citations), we get a full picture of the life and times of Clair Bee.

And in the process we get a good look into many fascinating annals of basketball history, such as where the three-second-in-the-lane violation comes from, who popularized the one-handed shot, the inside story of the battle for integration of college basketball, and much, much more.

He also gives us a bit of the dark side of big-time college sports—the stuff avid fans, myself included, should, but don’t really want to, think about—such as the use of illegal, performance-enhancing drugs, the influence of big money on college sports, hazing and bullying, and the increasingly blurry line between amateur and pro.

The book could be shorter and more concise, but clearly Gildea wanted to be thorough, giving the anti-Bee side enough elaboration so that his pro-Bee conclusions would stand more firmly. And thorough he is, conducting copious interviews with people who had professional and personal relationships with Bee and his contemporaries, poring over volumes of newspaper and magazine articles of the period, and probing deeply into sports statistical records.

As a writer, Gildea seems a bit old school. The book has a formality and distance of an earlier time, much as if it had been written back in Bee’s day. For example:

“But basketball was to be included in the Berlin Olympic Games later that summer for the first time in Olympic history, and the American Olympic Basketball Committee, under the direction of J. Lyman Bingham, had plans in place for a nationwide qualifying tournament that would culminate with eight teams meeting for the final rounds to be played over three days in the Garden.”

Yet if you have a basketball jones, this book will slake your craving for hours on end. And when you’re done, pick up a “Chip Hilton” book and see for yourself why millions of young men agreed with the publisher’s slogan: “Clair Bee—He knows what makes boys tick.”