The Lair

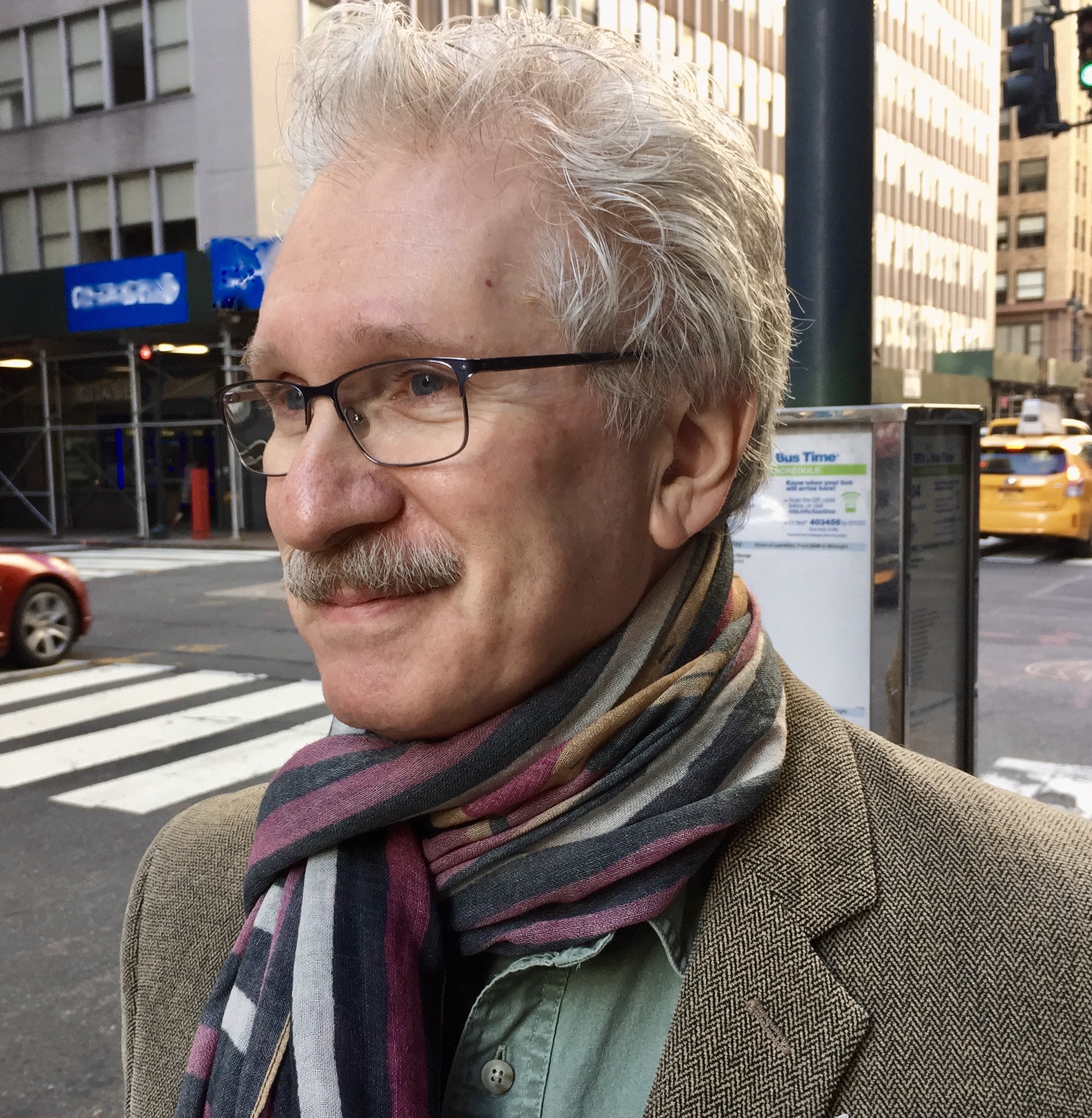

by Norman Manea

Yale University Press

The first short story published in the United States by Norman Manea appeared in TriQuarterly two decades ago and was then included in his first American book, October, Eight O’Clock: Stories (1994). The most important Romanian writer of our time, Manea was forced out of his native country in 1988 and has lived in exile ever since—briefly in Germany and then in the United States. His memoir The Hooligan’s Return (2003) narrates his first trip back to Romania. The reign of Nicolae Ceaușescu had ended in 1989, when a revolution overthrew and killed him and his wife, his assistant in absolutism. With admitted trepidation, Manea enters the dead monsters’ domain and finds unease, ruin, sadness, grief, memories, lost opportunities of life, and the monster’s minions—successfully resisting the demise of the despotic rulers’ regime. Manea’s earlier novellas, collected in Compulsory Happiness, and novel, The Black Envelope (both reissued in paperback this year by Yale University Press), treat life in the distorted and distorting society that evolved under Ceauşescu’s insane and powerful control.

Manea has portrayed lived contradictions with great imaginative energy, and this is especially true of his two new books, the novel The Lair (translated by Oana Sânziana Marian) and a new collection of essays, The Fifth Impossibility (many translators). Both of these have recently been published by Yale University Press. The former is the first novel that Manea has set in the United States—but our society is only a backdrop, albeit a very rich and difficult one, for an elaborate, intricate, delicate narrative structure, balanced just so, that holds within it the riddles of identity among exiles, the persistence of old, violent illusions, and the cherishing of friendship when no friend is fully loyal. As Manea himself has said, this is not an American but a middle-European novel: a free movement of narration and thought through the labyrinthine corridors of intersecting lives—friends, enemies, lovers, thugs, accomplices to dictatorship, and doubters of freedom. The Lair shows us life as a richly incomplete and unresolved experience. (I think there’s a still potent heritage of ancient Mediterranean cultures in this sense of the incompleteness and impossibility of resolution in life; this is certainly not an American idea.)

In the new book of essays, The Fifth Impossibility, Manea tells stories too, and does so with compelling subtlety and insight. In “The Incompatibilities,” he describes the bizarre turns in the life of the Romanian writer Mihail Sebastian, as recorded in the latter’s posthumous Journal: 1935–44. The freezing anti-Semitism even of Sebastian’s friends and the ineluctable descent into social madness are part of what Manea calls the “obscene decade”; yet in Sebastian there was also a sweetness of temperament. Elsewhere, Manea calls this journal an even greater work than Victor Klemper’s incredible diary of the Nazi era in Dresden. In the sense that “incompatibilities” provide the basis for all judgment, Manea shows—as he has in other works—that when no one finds anyone else or anything else that is incompatible with his own wishes and impulse to survive, then the likelihood of survival as a fully human being becomes very small. Everyone accommodates himself, his values, his choices, to the power of others so as to preserve what little choice he himself has. (We are used to thinking of our own political incompatibilities as what prevents our ever achieving rational solutions to social and economic crises and evils; but Manea shows us the contradiction and degradation that are created by the absence of any sense of incompatibility.) In “The Walser Debate” and elsewhere he proposes that to accompany existing public monuments to past heroic figures and events that we must admit—if we are to be honest—are often dubious or even horrifying, all nations should also create “monuments of shame.” These would publicly acknowledge ignominy too, and in that way “the state [might] finally be compelled to reconsider its role and aspire to the highest good, namely the unconditional respect of the rights of the individual.” If we should deplore “collective guilt,” Manea shows, we should also deplore our equally unthinking “collective heroism.” Indeed.