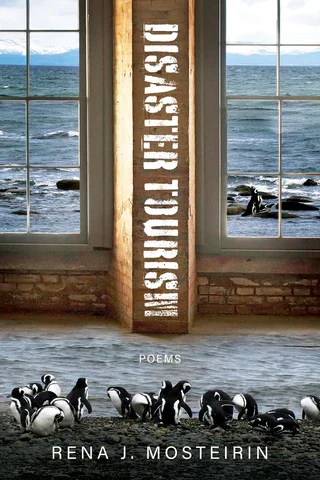

A Review of Disaster Tourism by Rena J. Mosteirin

Rena J. Mosteirin’s debut full-length poetry collection Disaster Tourism takes readers on a visceral and existential journey to explore what it means to inhabit a world inundated with individual threats and systemic violences. From war, racial profiling, housing insecurity, global warming, and mass shootings, Mosteirin’s poetry helps us turn over every facet of what it means to live in inevitable danger. Her attention to embodied language and how she integrates contemporary events with the greater landscape of cultural-generational memory are the core engines of this poetry collection’s impact.

Disaster Tourism is organized into three parts: “An Alarm,” “No Home,” and “The Encrypted Latina.” Each of these sections draws us into different dimensions of the speaker’s life, underscoring the interconnectedness of small- and large-scale disasters.

The first section, “An Alarm,” details a formative memory for the speaker: “I once saw two police officers shoot a Hawaiian woman dead” (11). The speaker in that moment was not able to scream out for help:

“No alarm went off for her

and that’s when I realized

my own vocal cords were cut” (11).

Looking back on this horrendous moment of police violence, it is easy to lay blame on oneself for inaction. At the core of this event is a systemic issue of police using racial profiling and a lack of accountability for using extrajudicial force. The speaker dives deeper into this issue in the following poem, “Her Name”: “[t]here was no outrage because she was brown” (13) and there were no cell phones at that time that could capture “the police actually shooting her” (12).

The speaker, as a brown woman herself, knows that the violence that edged up against her that night has the potential to come again in spaces of precarity and surveillance, the unfortunate state of living under constant threat. With so much clarity on what her younger self was willing to risk (or not), the speaker in many subsequent poems recognizes and brings attention to issues that might be uncomfortable for others to discuss, including racism, homelessness, suicide, drug use, incarceration, and sexual violence. What are we willingly ignoring that is urgent around us? What are the stakes of us looking away?

Alarms appear as a motif in Disaster Tourism, both literally and figuratively. The book begins with the image of a literal alarm used for emergencies in the first poem: “smoke alarm screwed in by the landlord / last year, now that the cheap batteries are dead / it chirps at a broken tempo” (11) and evolves into the natural “alarm clock” of a rooster’s morning call: “Roosters crow, I get it now. / It’s an alarm” (122).

In between these two poems, we move through the manifestations of “alarm” on the psyche and begin to track the origins of trauma that has appeared in the speaker’s everyday life:

"the Mexican teenager finished reading his poem and the tattooed, tight-jeaned,

short-haired,

white people of Knoxville, Tennessee stood up and cheered.

I was wrong to fear them but not wrong to fear” (19).

Fears are first encoded onto the speaker’s body, first by her parents who were immigrants, and we learn what generational warnings and traumas the speaker has inherited.

In the second section of the Disaster Tourism, “No Home,” the speaker conjures images of places that are unstable and claustrophobic, such as an emergency room, prison, or car, all which echo sentiments of a liminal space between home and a precarious, unfamiliar “other” place. These images link the speaker to connect her current traumatic responses to what came before her:

“We who are used to accepting

the disappearance of family members

find it easier to leave our families” (53).

She recounts the pain of forced migration, which her mother’s side experienced when Gottescheers were resettled after World War II. She references water and drowning, a link to her father’s story of fleeing Cuba. This section of the book contains poems that hold the tension of the speaker’s mother saying “[y]ou will never have a homeland” (62) juxtaposed with a soothing image: “can make [the speaker’s] face familiar / so everywhere you go, you will be welcomed home” (62).

It becomes difficult to reconcile the dual experience of being accepted in multiple cultures and countries because of outward similarities while also yearning for a place to state as the motherland. This hearkens back to the idea of walking through places as both a tourist and spectacle evoked by the term “disaster tourism.”

The final section of Disaster Tourism, “The Encrypted Latina,” explores the Cuban side of the speaker’s family. The idea of encryption adds a potential layer of illegibility to it, perhaps reflecting the necessity of survival coming in the form of hiding some information about one’s self, especially for refugees who face the threat of punishment in their home country. The poems range in style and length: some poems are driven by the songs the speaker’s grandparents’ loved into the last moments of their lives and other poems that sprawl across multiple pages to create a threading effect of associations and narratives. This section features more present-day poems featuring the experiences of the speaker’s life, showing the evolution of integrating multiple experiences into the current ones we are about to have.

Mosteirin’s Disaster Tourism will make you interrogate the land you stand on, who destroyed the lands your ancestors once called home, and how each of us is simultaneously a tourist and spectacle wherever we go. Mosteirin skillfully renders how global events ripple through each of us, making her collection urgent and timely, especially as we continually live through current-day assault on human rights, free speech, immigration, and blocking access to physical and mental health resources.

Disaster Tourism offers a lens for us to think urgently about community care and protecting each other as we experience personal and systemic violence. No one is immune to disaster. We can choose to heed the warnings or become more present with them. The speaker does not posit any panaceas for the ills in our lives, but it does present a mirror in which we can all look into to question our relationship to safety, home, politics, and the environment – all of which are deeply interconnected.

What we choose to do after looking into the mirror is up to us, but we must first look to acknowledge what our humanness is capable of, and what kind of actions we can sustainably take to fight tyranny and interrupt patterns that keep us trapped in a cycle driven by generational trauma.

Disaster Tourism by Rena J. Mosteirin

BOA Editions, 2025. 122 pages. $19 paperback.