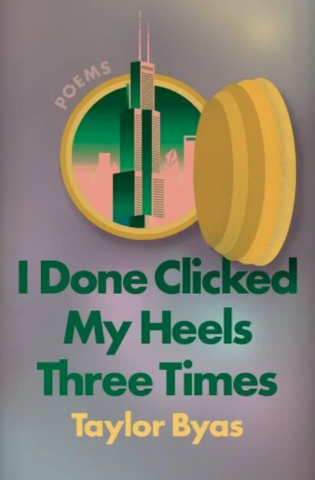

Poet Taylor Byas' new collection I Done Clicked My Heels Three Times: Poems came out this summer from Soft Skull. The following interview with Byas was conducted by TriQuarterly's nonfiction editor Starr Davis.

TriQarterly: This has to be one of the most iconic poetry collections written by a Black woman poet to date, it is so much more intentional, almost a mother figure in comparison to your other collections Bloodworm, and Shutter. So much of this collection is culturally aware of the ways in which Black womanism is a historical account of supreme intergenerational oppression. You mention accounts of therapy and healing processes in so many of the poems, therapy often being a jaded concept of the Black community. Can you talk about your forthrightness, the power of confessional poetics, and how therapy is a birthed experience in this collection?

Taylor Byas: First, thank you so much for your incredible compliment. I’m so proud of this book and the impact that it seems to be having already out in the world, and I’m so grateful for your time and attention to it. I love how you mention therapy as a jaded concept of the Black community, and I would take a step further to say that being confessional and talking openly about what we experience is also something the Black community still struggles with. So much of this book combats generational and cultural silences. And it created discomfort for some close family members. For some of these poems, which are so incredibly personal and vulnerable, I remember my mom’s initial reaction to some of them was defensiveness, wondering why I was still writing about things that were “over” and that we’d moved past. There is a knee-jerk reaction to cling to secrecy, to equate moving on or forgiveness with silence, and I wanted to undo that in this collection. Therapy was so central in that confessional mode because again, I want to subvert the idea that the Black woman is the superwoman that heals alone. Healing happens in community. Healing happens when we look down the barrel of the painful truths.

Taylor Byas: First, thank you so much for your incredible compliment. I’m so proud of this book and the impact that it seems to be having already out in the world, and I’m so grateful for your time and attention to it. I love how you mention therapy as a jaded concept of the Black community, and I would take a step further to say that being confessional and talking openly about what we experience is also something the Black community still struggles with. So much of this book combats generational and cultural silences. And it created discomfort for some close family members. For some of these poems, which are so incredibly personal and vulnerable, I remember my mom’s initial reaction to some of them was defensiveness, wondering why I was still writing about things that were “over” and that we’d moved past. There is a knee-jerk reaction to cling to secrecy, to equate moving on or forgiveness with silence, and I wanted to undo that in this collection. Therapy was so central in that confessional mode because again, I want to subvert the idea that the Black woman is the superwoman that heals alone. Healing happens in community. Healing happens when we look down the barrel of the painful truths.

TQ: I am thinking of how you drove storytelling in poetic forms centered around the repetition to relay yearning, like in your poem Men Really Be Menning, and how each beginning and ending line found its way trapped in a riddle of endless disappointment. I celebrate you in many ways as the queen of metaphoric magicalism. How has poetic form (s) become accessible to you, to your stories? And for those of us poets who might struggle with form (*coughs guiltily *) how do poetic forms become gateways in storytelling?

Byas: I want to linger for a moment on a definition of “magicalism” that I found; “the belief that a self’s realignment requires ceremonial initiation.” — Christian Relaunch

I’m drawn to this concept of ceremonial initiation, as I think there is something ceremonial about form, repeating forms in particular. With the “Men Be Menning” sonnet crown, for example, there’s a way that those repeated opening lines of each sonnet initiate a new opportunity for understanding, for transformation, for realignment. Of course, that transformation is delayed until the very end of the crown to imitate my own loop of disappointments when grappling with romance, but the potential is there! For me, form forces me to drive straight to the heart of language. I was a fiction writer first, and I can meander and stay in the details forever. Form talks a scalpel to ME. But for those who struggle with form, reframing how you think about it is the first step. So many people see form as the villain, the thing that will police the poem you want to write and how you want to write it. Form is your friend. Form will force you to get creative with language, line breaks, punctuation, white space. Form sends you searching for possibility, and isn’t that fun?

TQ: In this collection, many poems reference your grandmother, who in most Black families, is the pillar of strength and wisdom. Can you talk about her symbolism in this collection, and how she represents home for you?

Byas: I have the best grandma in the world. She has been an exceptional example of what dedication and love look like, what Black women’s dedication and love look like in particular. If she can show up to something, she will be there. If she can do something special to celebrate an achievement, a win, a special day, she goes all out. Her well of love is endless. She is one of the most reliable fixtures in my life. I think that’s what really moves me about her, the knowledge that she will be there, never having to doubt or question it ever. I hate to say it, but it’s much harder in this life for Black women to experience a love like that, and I feel so grateful to have at least one model of what that kind of love and care looks like.

TQ: I first read this collection when I was running from something or someone I should say, and I think it has a lot to do with the pandemic. I think this collection speaks to the idea of escapism, or being triggered by memories that take us back to places and people. Has safety in your relationships with poetry, people, and the world, especially as a Black woman, changed in any way since the pandemic?

Byas: Whew, safety in relationships. Since the pandemic, some of these relationships feel safer, and some feel more dangerous. I think people are really struggling right now. I see it in my friendships, with family. There is a fog of grief moving quietly through all of our lives, and we’re all trying to navigate these new realities. As a result, it’s harder for people to be in community and to show up for one another. Connection with people feels less safe, less reliable. The world feels less safe. But I feel an increased safety in my poetry these days. With the debut out, and with the second book also under contract and slated for release in 2025, I’m in this really cool space with my writing where I’m not writing towards anything and I don’t feel pressured to do so. I feel freer in my writing than I’ve ever felt. I don’t feel worried about individual publications, or feel the need to rush to get anything “ready” to send out. The page has been so quiet, so open for anything I want to plant. What a gift it is to be here.

TQ: I wondered about the idea of reparenting oneself and how memories of your mother and father haunt you in this collection. The poems, mother, and although, both stuck out to me as fascinating accounts of the methods in which Black girls are raised in survival-mindedness. Can you explain the nuances of surviving childhood in Chicago, and how those methods have affected you in adulthood?

Byas: The thing is, for the Black woman, there are ways that location matters and then in some ways, there are ways that some experiences will find the Black woman no matter where she is. Surviving Chicago was more about surviving what it made of its young boys and, ultimately, its men. But that isn’t a “Chicago” problem either. Take one look at any social media feed and we’re bombarded with what this world is making of Black men, the violence we deal with, the violence we are expected to shoulder and tolerate to find love even. At the heart of this book, there is a lot of violence from men, including my father. At the end of the book, I sort of accept that I’m still learning what love looks like, that I still have so much to learn. More than anything, I think those violences growing up continue to make it really difficult to welcome love and to recognize it.

TQ: To piggyback off the idea of survival, let’s talk about dating while Black, or while Black and woman is a thing. Poetically you have my attention in Paying for Hotels and Men Really Be Menning. Can you speak on boldness and vulnerability in poetry, and how you approach these conversations with sexuality and dating in some of the poems in this collection?

Byas: Often times our default emotions are shame and embarrassment when dealing with our dating experiences as Black women. And how could they not be, when the world finds every way to blame us for our singleness, for suffering abuse, for being cheating on, left, etc. It’s so easy to internalize those narratives and to think we are responsible for the way men treat us. Writing about these betrayals in this book really helped me to see myself more objectively. I have a big father wound, and how that shows up for me in relationships is I think I have to work for and constantly earn love and affection. I feel solely responsible for maintaining a partner’s attention, and often feel like I always have to be doing something to keep it. It’s still hard, even after a lot of self work, to believe that I’m inherently worthy of those things. But writing about those dating experiences and being vulnerable in those ways helped me to start seeing how silly that thinking was. Here I was doing my best, being genuine, loving without being asked or prompted. Writing the poems were often an “OH” moment that I needed, and I think moments that can be healing for other Black women to experience too.

TQ: Lots of people may not have watched The Wiz, to understand the invitation of Blackness it offered to a generation that did not have the consistency of Black visibility in storytelling. The place Dorothy was thrust into was not a middle-of-nowhere experience, it was an urban fantasyland full of music, and also real terror. Those are also themes in this collection, lots of beauty, but also lots of real-time trauma. Using a solid storyline such as The Wizard of Oz, as an outline for a poetry collection is pure genius. How did this movie spark this collection?

Byas: I didn’t really start to think deeply about Chicago and about home until I left it, and I think there is something about The Wiz that speaks to that experience. After being forced away from home and into the unfamiliar and into terror, her understanding of home gets redefined. At the beginning of the movie, we see her conversation with Aunt Em, and it’s evident that Dorothy doesn’t like a lot of change and is comfortable where she is. Meanwhile, Aunt Em is anxious for her to get out and experience more in life. We don’t get to see what kind of decisions Dorothy gets to make when she returns home, but I can imagine that changing schools and moving out of her aunt’s house would feel like easy transitions to make after everything she experienced in Oz. Stepping away from Chicago helped me to reframe those experiences in a similar fashion. I also love the way that music moves us through the different phases of Dorothy’s journey, and I saw parallels between the music and the way the narrative of the book started to form. So we decided to use the songs as an organizing structure, and I really love how it helps to guide the reader through.

TQ: In these pages is a reality of the fears of womanism and tending to the body as our first home, especially in the poem Lump. You not only presented us with this poem, but on the following page, you created an erasure from the same poem. This is the first time I witnessed a poet create an erasure from their own poem in the same collection. I was like wow, I can feel the intimacy behind revision and reinvention. What are your thoughts on erasure poetry and the political movement of this form? And furthermore, how is it challenging you as a poet to press beyond the creative process and into the visual production of hybrid poetry?

Byas: Man, I love erasure. I love how it requires intimacy with a text, for you to become a student of a text in order to redact and erase it. It also feels powerful to engage with a text and reclaim a hidden narrative or excavate a perspective that was intentionally obscured, which is how I find myself most often engaging with erasure these days. To erase myself was so interesting because to do so is also admitting that I wasn’t telling the full truth the first time, that there are things that I was hiding even from myself. That kind of honesty is difficult to hold, even harder to get to. But the form sets the stage for that kind of intimacy. I’ve been thinking a lot about the different ways we approach erasure and how the visual choices we make also drastically impact the reading experience. I just read Nicole Sealey’s interview in The Brooklyn Rail about her new book The Ferguson Report, where she talks about the choice to leave the redacted parts of the report grayed-out, but legible if the reader makes enough of an effort to engage. Erasure challenges me to think more intentionally about the reader experience. Do I want to direct the reader towards or away from the source text? Is their experience deepened or distracted by my visual choices? It forces you to see the poem as more than a poem, but as an artifact, an exhibit.

TQ: The collection begins with your poem, South Side (I), “This teaches me love…” and the last poem in the book, Dear Moon, ends with “I’m still learning…” What I love about this echoing is the haunting reality that we are on a continual journey inside ourselves, levels to levels, realms to realms. Can you speak about the ways you differentiated Chicago and yourself both as characters and also, as one spirit?

Byas: Chicago and I are so similar in that we are both heavily defined by the outside world, we are both complex beings. We can be cold when we want to be. We never sleep. We are mothers worrying for our young, worrying after our dead. But Chicago relies on me to help tell her story, and to write it right. And so here I am, trying to tell the world about who she really is.